|

One of the most significant events of the Renaissance was the religious movement of the Sixteenth Century. This milestone, known as the Protestant Reformation, was the most serious upheaval in the Christian since the introduction of Christianity into Europe. It divided the Western into two opposing factions and produced the various evangelical branches of Protestant Christendom.

Primarily, this revolution was neither political, philosophical, nor literary. It was emphatically a revolt that was centrally religious and idealistically moral in its motivation. The Reformation, however, did achieve revolution in politics, philosophy, literature, art, and music in the end, although it was not begun for the sake of these aims.

The Reformation was not an abrupt revolution, because it had its roots in the Middle Ages. There were many forces during the late Medieval centuries that were especially conducive to the rise of reform within the Christian Church: the unification of some European nations, the founding of universities, the revival of learning on a broad scale, the new astronomy of Copernicus, and the return to Greek philosophy as a source of wisdom. Within the Church itself there were sufficient reasons for religious revolt. The Church was troubled with moral, financial, and political scandals. Grievances against such acts as these and the failings of Church authorities to address such problems ultimately compelled some to face the risk of heresy by questioning the Church’s doctrines and temporal practices. The true greatness of the Protestant Reformation may lie less in what was actually done at the time the Reformation began, since it was essentially a laying of the cornerstone of Protestant faith, than in the much greater work that it made possible in successive centuries.

Much profound thought of the last four centuries, even in the Roman Catholic countries of Europe, has been a direct or indirect result of the Reformation. The movement in Germany was probably the most influential and extensive of the Sixteenth Century revolts against the Catholic Church. The German Reformation was directed by a man of considerable genius and great energy, Martin Luther.

Luther was born November 10, 1483 in Eisleben, Thuringia (a province noted for its many musicians even up to the birth of Johann Sebastian Bach). Luther was brought up in the strict religious atmosphere of the German Church. He was the son of a prosperous miner, who had educational ambitions for his son to become a lawyer. After attending the Latin Schools at Mansfeld, Magdeburg, and Eisenach, Luther entered the University of Erfurt in 1501. From this institution he received the Bachelor’s degree in 1502 and the Master’s degree in 1505. Following his father’s wishes, Luther began to study law. However, during his student years, Luther was increasingly troubled by thoughts of the wrath of God, and he continually sought a means of finding inner peace.

To achieve this, he entered an Augustinian Monastery on July 17, 1505 to become a monk. Two years later, he was ordained as a priest. In 1508 Luther was appointed Professor of Philosophy at Wittenberg University, and he also studied there subsequently to receive the Doctor of Theology degree in 1512. Upon the completion of his doctorate, he was appointed Professor of Sacred Scripture, a post which he held until his death in 1546. In 1515, Luther was appointed Augustinian Vicar for Meissen and Thuringia. Three years later he was commissioned to visit Rome to plead the cause of the reorganization of the Augustinian Order. While in Rome, Luther was shocked by the worldliness of the Italian clergy.

During the period of his appointment as Vicar, Luther underwent a modification in his views and beliefs. He was still devoted to the Church, but in his continued quest for inner peace, he turned from religious philosophy to the Bible as the basis of his theological conclusions. Luther came to believe that the essence of the Gospels is faith in the crucified and risen Christ and that the sinner is “justified by faith alone.” Justification by faith became the touchstone of Luther’s theology, and as he began to come to terms with the doctrine and its implications, he carried most of the university faculty with him. Wittenberg became known as a center of Biblical studies, and Luther’s theological conclusions ultimately led him to question some doctrines and practices of the Church. Since Luther’s theology was based on the Scriptures rather than on Church traditions, conflict with Rome was inevitable, and Luther was eventually branded a heretic and was excommunicated for his radical defiance of Papal authority in the Bull, Exsurge Domine.

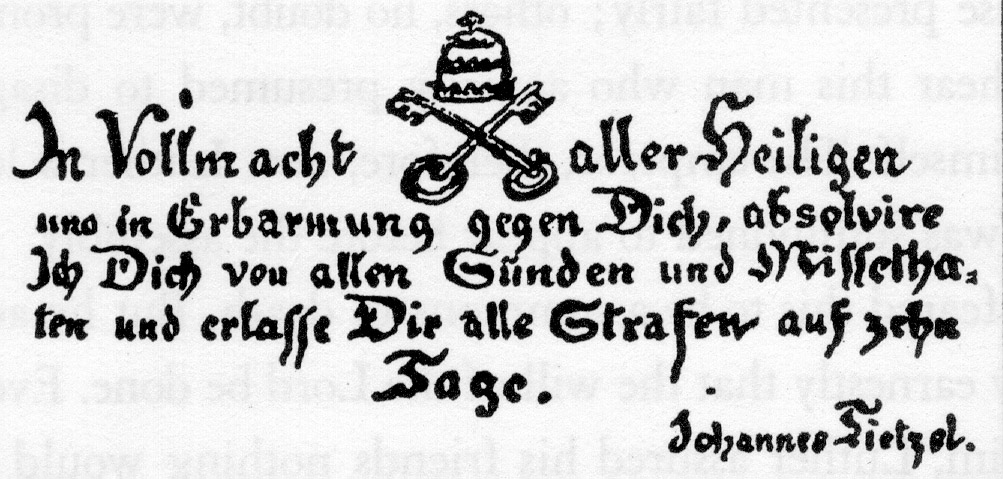

Pope Leo X’s authorization of the sale of indulgences for sins by Johann Tetzel (Johannes Tietzel) at a Church near Wittenberg incited Luther into action. On October 31, 1517, he nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the Castle Church door at Wittenberg. This was not intended as a decisive attack on the Church, and he did not wish these writings to be circulated outside of Wittenberg. However, the news spread throughout Germany within a period of two weeks.

Translation: “In the authority of all the

saints, and in compassion towards thee,

I absolve thee from all sins and misdeeds,

and remit all punishment for ten days.”Johannes Tietzel

Later in 1518, Luther publicly professed his implicit obedience to the Church, but simultaneously, he boldly denied the absolute power of the Pope. Due to the slow means of communication, the events that followed this act took place within several years. There was not an immediate conflict with the hierarchy of the Church. However, on April 16, 1521 Luther was brought before the august meeting of the Holy Roman Empire, known as the Diet, at Worms, Germany. He was asked whether he acknowledged his writings and public statements. Luther requested a day for consideration of his answer. The next day, he replied that he would retract nothing written or said unless he could be shown through Scripture that his writings and statements were in error. He ended his brief speech with the sentence: “Here I stand, God help me!” Luther left Worms on May 25, having been declared an outlaw of the Church. He was seized by the Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise, and taken to Wartburg Castle near Eisenach. There he remained in hiding under the assumed name, “Squire George.”

It was during his long stay at Wartburg Castle that Luther began his work as a reformer. One of his first projects was to translate the Bible into German. A New Testament translation was printed in 1522. Meanwhile, the Wittenberg Augustinians had begun to change the worship service and to do away with the Mass altogether. This displeased Luther greatly. He returned to Wittenberg, and he spent most of his remaining lifetime carrying out a gradual change in the form of the worship service. The Protestant Reformation was now fully underway. In spirit and inwardness, it had not been conceived as anti-Catholic, but ultimately a separate and distinct Protestant Church was formed in Germany.

Luther’s preaching of “justification by faith,” the theology of forgiveness of the individual, became the central emphasis of all his reforms. Indeed, the importance of the individual and his salvation formed the basis of all of Luther’s writings, and his musical reforms also stemmed from this same frame of reference. Perhaps more than any other Christian teacher, Luther had the genius and the failings of an artist, but he ascribed the highest rank for music among the arts when he stated: “Next to the Word of God, the noble art of music is the greatest treasure in the world! The riches of music are so excellent and so precious that words fail me whenever I attempt to discuss and describe them.”

It is with music as well as theology that Luther brought about sweeping reforms in the German Church. Luther’s early training and experience with music had a profound effect upon his musical reforms. As a child, he was constantly exposed to music in his little Thuringian village. He remembered all his life how his mother loved to sing. Luther was trained to become a Kurrende singer: a chorus that went from house to house singing for weddings and funerals. Although the music Luther learned in the boy choir catered to peasants, he was later to be exposed to the great music of the Netherlander masters such as Okeghem, Isaac, Obrecht, and especially Josquin Des Prez, whom Luther greatly admired. He once stated: “Josquin is a master of notes, which must express what he desires; on the other hand, other choral composers must do what the notes dictate.”

The technique and style of Gregorian chant clearly influenced Luther’s work with music. He loved the Latin hymns and later revised many of them for service in Evangelical worship. Although he attacked all the impurities of the Roman Church, he never lost his high regard for its musical traditions. As for the music of his German contemporaries, Luther may also have been influenced by such German composers as Heinrich Fink and Adam von Fulda. And it is unquestioned that he maintained a long correspondence with his friend Ludwig Senfl, the most famous composer in Germany during Luther’s lifetime (although Senfl worked for the Dukes of Catholic Bavaria). In addition to his ability as a singer, Luther also acquired considerable skills on the lute and the flute (recorder), and at different times during his period of reforms, he worked with significant musicians, including the large body of singers and instrumentalists that Frederick the Wise employed at the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg. He also had close associations with the organists Georg Planck in Zeitz and Wolf Heinz in Halle, with the music publisher Georg Rhau and his assistant Sixtus Dietrich, as well as with the two successive Kapellmeisters to Duke Frederick, Conrad Rupsch and Johann Walther. It is with Walther that Luther collaborated later in his reforms to create a polyphonic chorale motet based on his most famous chorale melody, Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott. It is evident that Luther was a strong supporter of art music within the Church, for he stated:

“This precious gift [music] has been bestowed on men alone to remind them that they are created to praise and magnify the Lord. But when natural music is sharpened and polished by art, then one begins to see with amazement the great and perfect wisdom of God in his wonderful work of music, where one voice takes a simple part and around it sing three, four, or five other voices, leaping, springing round about, marvelously gracing the simple part, like a folk dance in heaven with friendly bows, embracing, and hearty swinging of partners.”

When Luther began his reforms of the Mass, the German Church had, to a limited degree, already developed a musical tradition of its own. It had been the custom for centuries to sing tropes and sequences (little hymns) in services in connection with the Amens, Kyries, and Alleluias. The German language was already employed with familiar parts of the service such as the Ten Commandments, the Seven Last Words, and some Psalms. But more importantly, German was regularly used as the language for the Credo (Creed) and the Lord’s Prayer. In addition to these musical settings to simple melodies, the congregation had many folk tunes and semi-religious songs called Leisen. Most of these songs were sung in unison in the style of Gregorian chants.

Luther underscored a new basic structure of worship: the action proceeds from God, not from human beings. Christ distributes his Body and Blood with the help of bread and wine, but each person receives these gifts. From this orientation arose Luther’s fundamental criticisms of the late Medieval Mass. This notion shaped the Medieval Mass: that the priest presents the elements of the Lord’s Supper as an offering to God and thereby demands from God the fruits of the Mass for the participants and for those absent (living and dead) for whom the Mass was endowed. This notion made possible Masses without the participation of the congregation. At the end of the Middle Ages endowments of Masses multiplied in order to reduce the punishment in purgatory. Frequently altars were endowed at which the “altarists” read Masses for particular persons in exchange for a living or a cash payment. The Castle Church in Wittenberg (dedicated in 1503 and completed in 1509) included nineteen side altars, at which nearly 9000 Masses were sung or read in 1519 alone.

These notions, erroneous in Luther’s view, also lifted the priest above the parishioners, since he was granted the ability to change bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ and thereby to effect something before God. The change in elements brought about by the priest was to a certain extent understood as a magical act, in which the Words of Institution assumed the function of a magic formula. Some feared that the Words of Institution would be learned by the laity and then used by them to effect this very change. To prevent this, they were kept secret and spoken only in silence. Luther led the fight against the sacrificial character of the late Medieval Mass on the basis of pastoral responsibility. He attacked it because it gave Christians a false sense of security and thereby became their undoing. With this he struck down all attempts to earn God’s grace through so-called “good works.” He held firm to his conviction that faith in Jesus Christ alone justifies. Therefore, he found it necessary to make changes in the liturgy based on this belief.

However, Luther’s intent was to retain and expand upon a tradition that was already in existence in German Churches, rather than to destroy musical and liturgical practices outright. He was not the founder of congregational singing as some believe, but there is no doubt that Luther established the practice of congregational singing of hymns and the Mass as a regular means of worship. Luther set about to gather music into the service of the Church. He wished to retain the richness and drama of the ancient Mass. However, it was in a gradual process that he found sweeping changes necessary, but in the end the heart of the Mass was preserved in Lutheran worship. In both his Latin and German Masses, Luther continued the basic liturgical tradition of the Medieval Church, changing only that which he found contrary to his understanding of the Gospel. Two places where his understanding conflicted with the Mass under the papacy were the Canon of the Mass and the Offertory. Otherwise, anyone who was familiar with the Medieval Mass would have found the Evangelical Mass quite familiar.

When, in 1526, Luther introduced the publication of his German Mass, he urged that it be used only in congregations where the majority of members no longer understood Latin. Liturgical orders, he concluded, should be maintained for the sake of growth in faith. “It has never been our intention to abolish the liturgical service of God completely, but rather to purify the one that is now in use.” The table which follows offers a comparison of the outlines of the Mass under the papacy, Luther’s Formula Missae, and his later Deutsche Messe.

| Mass under the papacy | Formula Missae, 1523 | Deutsche Messe, 1526 |

| Confiteor | (Prayers to Saints, the Virgin – Deleted) | (Prayers to Saints, the Virgin – Deleted) |

| Introit | Introit | Hymn or German Psalm |

| Kyrie (9-fold) | Kyrie ( 9-fold ) | Kyrie (3-fold) |

| Gloria in Excelsis | Gloria in Excelsis | Collect |

| Salutation and Collect | Collect | Epistle |

| Epistle | Epistle | German Hymn |

| Gradual/Alleluia | Gradual/Alleluia | Gospel |

| Gospel with acclamation | Gospel | Creed (Sung in German) |

| Homily (optional) | Nicene Creed (Sung in Latin) | Sermon |

| Nicene Creed | Sermon | The Lord’s Prayer |

| Offertory and the secret | Preparation of Elements | Admonition to Communicants |

| Preface | Preface | Words of Institution |

| Salutation; sursum corda | Words of Institution | Distribution of Elements |

| Sanctus | Sanctus | Hymns during Communion (German Sanctus, Agnus Dei) |

| Canon (Eucharistic Prayers) | The Lord’s Prayer | Collect |

| Benedictus | Agnus Dei | Aaronic Benediction |

| Agnus Dei | Communion distribution | |

| Communion antiphon | Post-Communion | |

| Communion distribution | Collect | |

| Post-Communion | Benedicamus | |

| Salutation/Benedicamus/Benediction | Aaronic Benediction |

In 1523, Martin Luther’s Formula missae et communionis pro ecclesia Wittenbergensi was published. It was a documented and detailed description of the Evangelical Mass as it was currently being celebrated in Wittenberg. It was sung in Latin, and it was essentially a purified version of the traditional Roman Mass. The only parts in German were the scripture readings, the sermon, and a few hymns. However, in the preface to this publication, Luther expressed the hope that a completely German service would soon follow, and he called upon the poets and musicians of the Church to enlarge the scanty store of good German hymns.

The idea of a completely German liturgy did not originate with Luther. The year before the Formula Missae publication, services were done in the vernacular in Basel by Wolfgang Wissenburger and by Johann Schwebel in Pforzhiem. Also in 1523, Kaspar Kantz, prior of the Carmelite monks of Nördlingen, published the first musical setting of the Mass in the German language. Later in the same year, Thomas Münzer published, not only a musical Mass in German, but also a Matins and Vespers service, elaborately printed with all the original Gregorian melodies. Other versions of a Mass in German were introduced in 1524 in Reutlingen, Wertheim, Königsberg, and Strassbourg.

The multiplicity of vernacular Masses threatened confusion; so Luther’s friends appealed to him to submit his own “blueprint” of a German Mass to bring uniformity to liturgical practices. Luther objected to the idea of a forced uniformity because he felt that each center of the Evangelical Church should be free to create its own liturgy, borrow from others, or maintain the Latin Mass, at least in part. Nicholas Hausmann of Zwickau suggested the formation of a council to establish liturgical uniformity. In Luther’s view, Evangelical freedom was not to be used as a pretext to establish a new legalism. Furthermore, the strongest reason for Luther’s hesitancy to endorse any available musical setting was his own integrity as a musician. He wanted the German Mass to be truly German, for he wrote in his pamphlet published in 1524, Against the Heavenly Prophets:

“I would gladly have a German Mass today. I am also occupied with it. But I would very much like it to have a true German character. For to translate the Latin text and retain the Latin tones or notes has my sanction, though it doesn’t sound polished or well done. Both the text and notes, accents, melody, and manner of rendering ought to flow out of the true mother tongue and its inflection also. Otherwise, all of it becomes an imitation in the manner of the apes.”

With the aid of two musical collaborators, Conrad Rupsch and Johann Walther, Luther’s project became a reality. Rupsch was employed as the Kapellmeister to the Elector of Saxony, and Walther came from Torgau where he served as cantor at the same court. Walther is remembered by history as the more important of the two composers, not only due to his composition of sacred polyphonic motets, but also because he is responsible for much of our knowledge of Luther as a musician. The two men stayed with Luther for three weeks in Wittenberg, and the 1526 publication of the German Mass, Deutsche Messe und ordnung Gottis dientis (German Mass and Order of Divine Service), was the result of their labors. Walther stated that during the work on the German Mass, Luther himself composed several Gospel lessons, Epistles, and the Words of Consecration of the Elements with the aid of his flute. Walther notated the music as Luther played and sang.

Deutsche Messe, 1526

|

In its final version, Deutsche Messe contained the following alterations to the pre-Reformation service as it was performed in Wittenberg. The Introit was replaced by the singing in German of Psalm 34: Ich will den Herrn loben … Meine Seele soll sich rühmen (Psalm 34:2-3) and following. The Kyrie Eleison was sung three times instead of nine.

|

Following the Collect and Epistle, a German hymn, Nun bitten wir den heil’gen Geist (Now We Implore God the Holy Ghost), or another with a similar text was sung. After the Gospel lesson came the German Credo: Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott (We All Believe in One True God), a tune widely known before the Reformation. The sermon was followed by a musical paraphrase of The Lord’s Prayer and an exhortation to the communicants. The singing that followed the Words of Institution was either Jesaia, dem Propheten, das geschah (Isaiah, Mighty Seer, in Days of Old), Jan Huss’ hymn, Jesus Christus, unser Heiland (Jesus Christ, Our Blessed Savior), or Christe, du Lamm Gottes (Christ, Thou Lamb of God), a pre-Reformation adaptation of the Latin text of a Gregorian Agnus Dei.

The extent to which Luther changed the Mass can be seen by looking at the music itself and the directions for performing it. It is obvious that Luther avoided the use of Gregorian melismas in his German chants. In his directions for the Introit he wrote: “For the Introit we shall use a Psalm, arranged as syllabically as possible.” Deutsche Messe was not designed to be a choral masterwork for the priests and choir to sing. It was conceived purposefully as a musical work for the congregation, priest, and choir. Luther’s musical reforms were centered on the inclusion of all believers in corporate worship, not just for skilled musicians and their musica reservata that was common before the Reformation. This does not imply, however, that Luther was in any way opposed to elaborate musical settings, but it was rather a recognition that not all Churches could maintain the services of highly skilled singers and instrumentalists. Where it was possible, Luther embraced the cultivation of music to the highest art possible. He enthusiastically supported the refinement of musical arts within the Evangelical Church. Luther’s own practical involvement with the creation of new music was matched by an understanding of music theory, which is evident from frequent references in his writings to the Quadrivium, the Medieval fourfold division of mathematics study into the areas of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music.

However, Luther’s Deutsche Messe possessed limited, rather than universal significance. Its main value lies in its idiomatic use of the German language and the impetus it gave to congregational song. It was prepared largely for the uneducated laity, the village volk, in Churches where there were no trained choirs capable of singing the traditional Latin chants. The creators of Deutsche Messe did not use Medieval ligatures in their musical notation, as was still a common practice for chant notation of the time. However, the chants were written in the Medieval church modes, and the Reformer assigned certain modes to specific parts of the Mass, for he wrote: “Christ is a kind Lord, and His Words are sweet; therefore, we want to take the sixth mode for the Gospel; and because Paul is a serious apostle we want to arrange the eighth mode for the Epistle.”

Luther developed his Introit, Psalm 34, by reworking the first psalm tone. The Medieval model had two accented notes in both the mediation and the termination of the psalm tone, but Luther provided three accented notes. He also allowed word accents in the intonation section which was definitely contrary to Gregorian musical practice. With these alterations, very little was left to be sung on the Psalm’s reciting tone. In his cadences, Luther adapted the music to the text by taking many liberties. What he produced was music that followed the rhythm of speech more closely than did Gregorian Psalmody. However, there was one great drawback, the difficulty of adapting Luther’s tailor-made music for Psalm 34 to other Psalms. Luther’s Introit did not function as a generic or easily adaptable psalm tone. This is a probable reason that it was never widely used elsewhere.

The Kyrie eleison of Deutsche Messe was based on the first psalm tone also. Here Luther greatly shortened what was a very elaborate Ordinary in the Roman Mass. Being totally syllabic, it is impossible to tell if Luther derived his Kyrie from a Gregorian example due to its very simple construction. In the music for the Epistle, the inflections are based on the eighth psalm tone, but the tonality is almost the modern F Major. The reciting tone is again neglected with emphasis placed on the inflections. In comparison to traditional Roman settings of the lessons, Luther’s music is more “melodious,” has a greater range (a seventh), and uses wider intervals. An additional musical example of an Epistle is given at the end of Deutsche Messe. Because the music of the final Epistle setting is simpler and more consistently constructed, it is believed that Walther most probably composed it.

For the chanting of the Gospel lesson, a feature from the Gregorian model for chanting the Passion Story was borrowed. This was the practice of having three separate reciting tones: one for the Evangelist (the note A), one for Christ (the note F), and one for all other persons (the note C). Although the music for the Gospel is in the fifth mode, the words of Christ are composed in the sixth mode. Though this may seem to be a contradiction of Luther’s original statement on the use of the modes for the Gospel, it is evidence that the modes were no longer strictly adhered to in the musical practices of the Luther’s time. They existed as theoretical bases for composition far more than they were strictly followed by Renaissance composers.

Deutsche Messe contained one unique innovation, the singing of the Words of Institution, the words of the Holy Communion referring to the significance of Jesus’ body and blood of the New Testament. In the Roman Mass, the words were not sung but murmured. In Deutsche Messe they are written as a simple sequence of tones full of symbolism and mystery of the sacrament as Luther viewed it.

The German Sanctus, Jesaia, dem Propheten, das geschah (Isaiah, Mighty Seer, in Days of Old), is a paraphrase of Isaiah 6:1-4. This part of the German Mass seems to have been a favorite of Johann Walther because he said that it, more than any other section of the service, showed Luther’s mastery of adapting notes to the text. Luther deleted the traditional “Holy, Holy.” The melody rises and falls to accentuate certain words, and there is even a climax implied on the words “loudly raised the shout.” Although it is written in the Lydian mode, it sounds remarkably like F Major. The melody of the Sanctus is not at all similar to Gregorian chant, for there are very wide intervals used in its construction. The almost step-wise movements of the Gregorian Sanctus settings stand in stark contrast Luther’s work. Luther, identifying the musical model, states that his melody is a free adaptation of a plainchant Sanctus entitled In Dominicis Adventus et Quadragesimae in the Graduale Romanum. It is also noteworthy that the Sanctus was to be sung during the administration of Holy Communion, thus intensifying the act of taking the bread and wine.

There was no musical setting of the German Credo, Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott (We All Believe in One True God), given in Deutsche Messe, because it was already part of the service. It was the subject of many different musical arrangements and harmonizations by various composers, including everything from polyphonic motets for skilled choirs to monophonic congregational versions.

The collaboration of Luther, Walther, and Rupsch produced a musical and liturgical model that was intended only to be an example of how the Mass should be done in the German language. It was not intended to replace the Latin Mass in any way, but to help the uneducated laity understand the act of worship. Luther was adamant that it should not be adopted universally, for he wrote in the preface to Deutsche Messe:

“In the first place, I would kindly and for God’s sake request all those who see this order of service or desire to follow it: Do not make it a rigid law to bind or entangle anyone’s conscience, but use it in Christian liberty as long, when, where, and how you find it to be practical and useful.”

As far as Luther’s personal practice in Wittenberg was concerned, he continued to use the Latin Mass published earlier in Formula Missae. The precept of liturgical freedom was paramount in Luther’s thinking, thus creating a great elasticity in liturgical practice. The entire service could be in German; there could be a hybrid Mass, partly in Latin and partly German; or certain Mass Ordinaries could be omitted and substituted with chorales (hymns) with texts very similar to the Ordinary. All chorales except those substituted for Ordinaries were required to fit the season of the Church year.

Scholarly assessment of Deutsche Messe has been mixed since the time it was first published. Lutheran liturgical scholars, however, generally characterize it as a less rich liturgy, which follows less closely to the ancient Order of the Eucharist than his Formula Missae. Those Lutheran liturgies modeled on the 1523 Mass are richer in form and content than those that take the 1526 German Mass as their model. Furthermore, it was Luther’s insistence on liturgical freedom that largely caused his own musical composition, Deutsche Messe, to fall into disuse and relative obscurity in successive centuries. For the sake of the education of the young, Luther wanted his Formula Missae to continue being used, as it was in some regions of Germany until the early Nineteenth Century.