|

It is one of history’s curious facts that both Martin Luther, the great Christian reformer of the Renaissance, and Johann Sebastian Bach, the greatest of all Lutheran Church musicians of the Baroque Era, were educated as children in the same town of Eisenach, Germany. Historically, Luther stands as a titan among the religious thinkers of the 16th Century, and Bach’s 18th Century counterpoint is widely considered to be the pinnacle achievement in the development of contrapuntal music which had originated centuries before his time.

As a religious reformer, Luther was an enthusiastic supporter of music within the German Church, viewing music as a great gift from God. Ever since Luther penned his famous chorale, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,” some have speculated that the “fortress” in question was Wartburg Castle, which sits atop a hill in Eisenach. Dating back to 1067, the castle became the center of courtly life during the Middle Ages, and although it hosted many prominent noblemen over the centuries, Martin Luther, a monk hidden in its tower, was by far Wartburg Castle’s most famous resident. Luther stayed there for 300 days, during which time he translated the New Testament into German. However, Luther was not the only famous inhabitant of Eisenach.

Synonymous with musicians, the Bach family had developed a reputation for its many notable performers for more than two centuries when Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Eisenach on March 21, 1685, as the eighth and youngest child of musician parents. His father was not only a string player, but also a court trumpeter, and the town piper. And he was most probably J.S. Bach’s first music teacher. Bach shared more in common with Martin Luther than just attending the same school in which Luther had received his childhood education: he shared Luther’s attitude toward music, viewing it, above all, as a means of glorifying God. The Bach family trade was simply that of being musicians, and as a group, they had a rich musical lineage that extended far beyond the Eisenach branch of the family. It was said that almost every German town in the late 17th Century could boast of having at least one Bach as a musician.

Now revered as the greatest composer of the Baroque Era, Johann Sebastian Bach was known during his own lifetime primarily as a great organist, since most of his compositions were neither widely known nor published during his life. Bach’s musical genius manifested itself in many ways, but most particularly in his perfection of the fugue as both an instrumental and choral form, producing sublime music that was imbued with a balance of technical mastery and intellectual control. Bach’s output includes works in every musical genre of his time except for opera. He used preexisting instrumental forms, adding new dimensions of quality, complexity, and technical demands unmatched elsewhere in music. By the end of the 18th Century, Bach’s compositions had earned him an almost legendary fame and a unique historical position. Many regard Bach as the greatest of all Baroque composers, but undoubtedly, his compositions are acknowledged by all as the culmination of Baroque musical art.

The first posthumous account of Johann Sebastian Bach’s life, with a summary catalog of his works, was put together by his son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, and his pupil, J.F. Agricola, soon after J.S. Bach’s death and certainly before March of 1751 (published as Nekrolog in 1754). J.N. Forkel planned a detailed biography of Sebastian Bach in the early 1770s and carefully collected first-hand information on the composer, chiefly from his two eldest sons. The book was published in 1802, creating a growing public interest which ultimately led to the mid 19th Century Bach “revival” and to the publication of various collected editions of Bach’s works. Johann Nikolaus Forkel’s On Johann Sebastian Bach’s Life, Genius and Works presented the composer as a Teutonic hero whose keyboard works represented a German national treasure. Philipp Spitta, writing in the verbose style of 19th Century biographers in the 1870s, presented quite a different image of Bach. In his monumental three volumes, Johann Sebastian Bach: His Work and Influence on the Music of Germany, 1685-1750, Spitta painted a vivid, albeit highly romanticized, picture of Bach as the “Fifth Evangelist,” proselytizing for the Lutheran faith through his Cantatas and Passions.

Spitta’s view of Bach was widely accepted until the 1950’s, when a redating of Bach’s Cantatas revealed that Bach had written most of his sacred choral works during the first six years of his Leipzig period, and then, for the next 21 years, the composer primarily turned his attentions to other endeavors. The problem remains that J.S. Bach did not record the details of his life to any great degree, since he was so very busy as a father, teacher, organist, choirmaster, music administrator, and composer. He was not a prolific writer of letters, and only a few letters in his own handwriting survive to give us insights into his personality. This fact leaves the composer’s life open to varying interpretations on the part of his biographers. Therefore, the information provided by his son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, is likely the most accurate account of Johann Sebastian Bach’s life. Additionally, a substantial number of events in Bach’s life have been confirmed through careful examination of extant records of the various churches, courts, and municipalities where Bach worked.

Childhood

(Eisenach 1685-1695 and Ohrdruf 1695-1700)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s parents were Johann Ambrosius Bach (1645-1695) and Maria Elisabeth Lämmerhirt (1644-94), daughter of a furrier and town councilman in Erfurt, Valentin Lämmerhirt (d 1665). Another Lämmerhirt daughter became the mother of Bach’s cousin J.G. Walther. Elisabeth’s elder half-sister Hedwig Lämmerhirt was the second wife of Ambrosius Bach’s uncle, Johann Bach, organist of the Predigerkirche in Erfurt. Elisabeth and Ambrosius, who had worked in Eisenach since 1671 as a Hausmann and a musician at the ducal court of Saxe-Eisenach, were married on April 8, 1668, and the couple had eight children, five of whom survived infancy, as well as Johann Sebastian, the youngest, whose date of birth, March 21, 1685, was carefully recorded by Walther in his Lexicon, by Sebastian himself in the family genealogy, and by his son as the co-author of Bach’s official obituary. It is supported in church records with the date of his baptism as March 23, 1685, in the register of Saint Georg’s Church. His godfathers were Johann Georg Koch, a forestry official, and Sebastian Nagel, a Gotha Stadtpfeifer. The house in which J.S. Bach was born no longer exists, but it was a house on Fleischgasse (now Lutherstrasse) that Ambrosius Bach bought in 1674 after gaining Eisenach citizenship.

Since the time of the Reformation, all children in Eisenach were required to attend school between the ages of five and twelve, and although there is no documentary evidence of it, Sebastian Bach must have entered one of the town’s German schools in 1690. From 1692 he attended the Lateinschule, which offered him a sound humanistic and theological education. At Easter in 1693 he was 47th in the fifth class, having been absent 96 half-days. In 1694 he lost 59 half-days, but rose to the 14th rank and was promoted. At Easter in 1695 he was ranked 23rd in the fourth class, in spite of having lost 103 half-days (perhaps due to illness, but probably also due to the deaths of his parents). He stood one or two places above his brother Jacob, who was three years older and less frequently absent. Very little else is known about his Eisenach training, but he is said to have been an unusually good treble singer and probably sang under Kantor A.C. Dedekind at Saint Georg’s, where his father made instrumental music before and after the sermon and where his uncle, Johann Christoph Bach, was the organist. His musical education is a matter for conjecture: presumably, his father taught him the rudiments of string playing, but according to Emanuel Bach, his father had no formal instruction on keyboard instruments until he went to Ohrdruf to live with his brother.

Elisabeth Bach was buried on May 3, 1694, and on November 27, Ambrosius married Barbara Margaretha, née Keul, the daughter of a former mayor of Arnstadt. At age 35, she had already been twice widowed. Her first husband had been a musician, Johann Günther Bach, and her second a theologian, Jacobus Bartholomaei. Both marriages had taken place in Arnstadt, and she brought to her third marriage two little daughters, Catharina Margareta and Christina Maria, one child by each of her previous husbands. A month before Ambrosius’s own second marriage on October 23, 1694, he and his family had celebrated the wedding of his eldest son, Johann Christoph in Ohrdruf. The music on that occasion was provided by Ambrosius Bach, Johann Pachelbel from nearby Gotha, and other friends and family members. This was probably the only occasion on which (the then nine-year-old) Sebastian Bach met Pachelbel, his brother’s teacher. Barely three months after remarrying, on February 20, 1695, Ambrosius Bach died after becoming ill some weeks before this time. On March 4th, the widow appealed to the town council for help, but she received only the legal minimum due her, and as a result, the household broke up. Sebastian and Jacob were taken in by their elder brother, Johann Christoph, the principal organist at Ohrdruf.

Both were sent to the Lyceum. Jacob left at the age of 14 to be apprenticed to his father’s successor at Eisenach. Sebastian stayed on until 1700, when he was nearly 15, and thus came under the influence of an exceptionally enlightened curriculum. Inspired by the educational philosophy of Comenius, Sebastian’s education included such subjects as religion, reading, writing, arithmetic, singing, history, and natural science. Sebastian entered the fourth class probably in March of 1695, and he was promoted to the third class in July. On July 20, 1696, he was first among the seven new boys and fourth in the class. On July 19, 1697, he was first, and was promoted to the second class. On July 13, 1698, he was fifth, and on July 24, 1699, he was second and promoted to the first class in which he was fourth when he left the school on March 15, 1700 and went to Lüneburg.

In the published obituary of 1754, Carl Philipp Emanuel stated that his father had received his first keyboard lessons from Johann Christoph at Ohrdruf, and in 1775 in a reply to Forkel, he said that Christoph might have trained him simply as an organist and that Sebastian became “a pure and strong fuguist” through his own efforts. That is the likely circumstance since Johann Christoph is not known to have been a composer of very many works. The larger of the two organs at Ohrdruf was in almost unplayable condition in 1697, and Sebastian no doubt picked up some of his expert knowledge of organ building while helping his brother with these extensive repairs. Johann Christoph lived until 1721, and the brothers were on good terms, but little else is actually known about Sebastian Bach’s life during the Ohrdruf years, except that Sebastian probably taught himself composition by copying the works of several composers. Most probably he took this compilation manuscript with him when he went to Lüneburg. As for its contents, Forkel implied that the manuscript contained works by seven famous composers, but according to the obituary written by C.P.E. Bach, the manuscript contained works by Froberger, Kerll, and Pachelbel, as one might expect since Johann Christoph’s teacher was Pachelbel.

There are no indications in any of Bach’s surviving scores to establish a date when he began to compose for the first time, but it is reasonable to assume that it was while he lived in Ohrdruf, since his contemporaries and, indeed, his own sons began composing original music before reaching the age of 15. The earliest organ chorales in the Neumeister Manuscript, as well as such works as BWV749, BWV750, and BWV756, provide plausible examples of pieces composed around 1700. They are characterized by sound craftsmanship and observance of models provided by Pachelbel. In all of these early works, J.S. Bach endeavors to break away from musical conventions and find independent answers.

Luneberg

(1700-1702)

According to the school register, Johann Sebastian Bach left Ohrdruf “ob defectum hospitiorum” (for lack of board and lodging). Clearly Johann Christoph no longer had room for his brother, since his wife had given birth to two children in the years since Sebastian’s arrival, and by March of 1700, a third child was expected. According to local tradition, Christoph’s house was only a small cottage, ill-equipped for so many people. The problem seems to have been solved by Elias Herda, Kantor and a master at the Lyceum. He had been educated in Lüneburg, and no doubt it was he who arranged for Sebastian to go north. Similarly, Herda probably also helped Georg Erdmann, a schoolmate of J.S. Bach, three years older, who left the school for the same reason. According to C.P.E. Bach’s account, the two boys traveled together, and they must have reached Lüneburg before the end of March, since both were entered in the register of the Mettenchor (Matins Choir) by April 3, 1700. They probably sang in the choir within a matter of days for the Holy Week and Easter services.

The Michaeliskirche in Lüneburg had two schools associated with it: a Ritteracademie for young noblemen and the Michaelisschule for commoners. There were also two choirs: the “chorus symphoniacus” of about 25 voices was led by the Mettenchor, which numbered about 15 singers and was limited to poor boys. Members of the Mettenchor received free schooling at the Michaelisschule, up to 1 thaler per month according to seniority, their keep, and a share in fees for weddings and other occasions. Bach’s share in 1700 was recorded as being 14 marks. From the arrangement of the pay sheets, it has been deduced that both Bach and Erdmann were trebles. Bach was welcomed for his unusually fine voice, but it soon broke, and for eight days he spoke and sang in octaves. From that time, he made himself useful as an accompanist and/or string player.

Bach’s studies at the school included orthodox Lutheranism, logic, rhetoric, Latin and Greek, arithmetic, history, geography, and poetry. The Kantor was August Braun, whose compositions have not survived, and the organist was F.C. Morhard, about whom no details are known. The organ was repaired in 1701 by J.B. Held, who had worked at Hamburg and Lübeck. Held lodged at the school, and he may have taught Bach something about organ building. There was a fine music library, which had been carefully kept up to date. But whether choirboys were allowed to consult it is uncertain. If Braun made good use of it, Bach must have learned a great deal from the music he had to perform, but his chief interests probably lay outside the school. At the Nikolaikirche was J.J. Löwe (1629-1703), a distinguished but elderly musician.

The Johanniskirche was another matter, for there the organist was Georg Böhm (1661-1733), who is generally agreed to have influenced Bach substantially. It has been argued that the organist of the Johanniskirche would not have been accessible to a scholar of the Michaelisschule, since the two choirs were not on good terms, and Bach’s knowledge of Böhm’s music must have come later, through J.G. Walther. But Emanuel Bach stated in writing that his father had studied Böhm’s music, and a correction in a note to Forkel shows that his first thought was to say that Böhm had been his father’s teacher. This hint is supported by the fact that in 1727 Bach named Böhm as his northern agent for the sale of Partitas Nos. 2 and 3. This fact implies that the two were on friendly terms, and it is more likely that they became acquainted between 1700 and 1702 than at any later time.

Bach traveled more than once to Hamburg, some 31 miles away, where he visited his cousin, Johann Ernst Bach, who was evidently studying there about this time. The suggestion that he went to hear Vincent Lübeck cannot be taken seriously, for Lübeck did not go to Hamburg until August 1702, by which time Bach had almost certainly left the area. He may have visited the Hamburg Opera, then directed by Reinhard Keiser, whose Saint Mark Passion he performed during the early Weimar years and again in 1726. However, there is no evidence that he was interested in anything but the organ and, in particular, the organist of St Katharinen, J.A. Reincken. Reincken’s influence on the young Bach, both as a theorist and practitioner, would be difficult to overestimate.

J.A. Reincken (c1623-1722), a pupil of Sweelinck and organist of Saint Katharinen since 1663, was a father figure of the north German school of organists. Böhm may have advised Bach to hear him. Reincken’s showy playing, exploiting all the resources of the organ, must have been a revelation to one brought up in the reticent traditions of the south. As for the organ itself, Bach never forgot it. In later years he described it as excellent in every way, saying that the 32′ Principal was the best he had ever heard. He never tired of praising the 16′ reeds. Whether he actually met Reincken before 1720 is uncertain. If he did, Reincken might have given him a copy of his Sonatas. Bach’s reworkings of them, the keyboard pieces: Fugue in B-Flat BWV954, Sonata in a minor BWV965, and the Sonata in C Major BWV966, are more likely to have been composed soon after 1700 than 20 years later, when Bach no longer needed to teach himself composition.

Near the marketplace in Lüneburg was the palace used for visits of the Duke of Celle-Lüneburg and his court. The principal ducal residence and seat of government lay in Celle, some 50 miles to the south. The duke, married to Eléonore d’Olbreuse, a Huguenot of noble birth, was a pronounced francophile and maintained an orchestra consisting largely of Frenchmen, which played in both Celle and Lüneburg. Thomas de la Selle, dancing master at the Ritteracademie, next door to Bach’s school in Lüneburg, was also a member of the Celle orchestra. Emanuel Bach knew that his father was often able to hear this “famous orchestra” and by hearing it to become acquainted with French musical taste. It cannot be ruled out that Bach occasionally helped out as an instrumentalist when the court orchestra played in the ducal residence in Lüneburg.

The exact date of Bach’s departure from Lüneburg is not known, but it is likely that he completed two years of education and left school at Easter in 1702. It is unlikely that he remained in Lüneburg for any length of time after that, for he left without hearing Buxtehude, and he later took extraordinary pains to do so in the winter of 1705-1706. He probably visited relatives in Thuringia after Easter in 1702. It is definitely known is that he competed successfully for the vacant post of organist at Saint Jacobi in Sangerhausen (the organist was buried on July 9), but the Duke of Weissenfels intervened and had J.A. Kobelius, a somewhat older man, appointed in November. It is certain that Bach lived for a short time in Weimar, where he was employed at the court as a musician for the first two quarters of 1703. The court accounts have him listed as a lackey, but he described himself as a “Hofmusikant” (court musician). This was at the minor Weimar court, that of Duke Johann Ernst, younger brother of the Duke Wilhelm Ernst who was Bach’s later employer from 1708 to 1717. Possibly the Duke of Weissenfels, having refused to accept Bach at Sangerhausen, found work for him at Weimar. Another possibility is that Bach owed his appointment to a distant relative, David Hoffmann, another lackey-musician at the same court.

Of the musicians with whom Bach now became associated, three are worth mentioning. G.C. Strattner (c1644-1704), a tenor, became Vice-Kapellmeister in 1695 and composed in a post-Schütz style. J.P. von Westhoff (1656-1705) was a fine violinist and had traveled widely, apparently as a diplomat, and is said to have been the first to compose a suite for unaccompanied violin in 1683. Johann Effler (c1640-1711) was the court organist. He had held posts at Gehren and Erfurt (where Pachelbel was his successor) before coming to Weimar in 1678, later moving to the court about 1690. He may have been willing to hand over some of his duties to Bach, and he probably did something like this, because a document from Arnstadt, dated July 13, 1703, (where Bach next moved) describes Bach as the court organist at Weimar, a post that was not officially his until 1708.

Arnstadt

(1703-1707)

The Bonifaciuskirche in Arnstadt was destroyed by fire in 1581, and it was subsequently rebuilt in 1676–1683. The church then became known as the Neuekirche until it was renamed in 1935 as the Bachkirche. In 1699, J.F. Wender was employed to build a new organ for the church, and the work was partially completed before the end of 1701, making the organ usable, but with only limited stops. Andrea Börner was formally appointed organist on January 1, 1702, and the organ’s registry was completed by June 1703. As was customary, several prominent organists were asked to examine the instrument, but only Bach was named and paid for his work, and it was he who “played the organ for the first time” in the summer of 1703. Bach had many relatives who lived in Arnstadt, and his family name was highly regarded by the local citizenry. As a result of his impressive skills as an organist, on August 9 Bach was offered the post of organist at the Neue Kirche over Börner’s head. And Börner’s responsibilities were then limited to the music of the town’s other two churches.

Bach accepted the post as an 18-year-old on August 14, 1703. The exact date that Bach assumed his duties in Arnstadt is not known, and his exact address while living in the town has not been precisely established. But since his last board and lodging allowance was paid to Feldhaus, he probably spent at least that year in either the Golden Crown or the Steinhaus, both of which belonged to Feldhaus. Considering his age and the local standards, Bach was well paid, and his duties were light. Normally, he was required at the church only for two hours on Sunday morning, for a service on Monday, and for two hours on Thursday morning, and, according to his contract, his only specified duty was “to accompany hymns.” Therefore, he had plenty of time for practice and composition. Bach took as his models Bruhns, Reincken, Buxtehude, and certain good French organists. There is no evidence that he ever took part in any of the theatrical and musical entertainments of the court or the town.

Bach was in no position to put on elaborate choral music at Arnstadt. The Neuekirche, like the other two churches, drew performers from two groups of schoolboys and senior students. Only one of these groups was capable of singing cantatas, and that choir was supposed to go to the Neuekirche monthly in the summer. But there does not appear to have been a duty roster. The performers naturally tended to go to the churches that had an established tradition (which the Neuekirche did not have). Bach had no authority to prevent this, since he was not a schoolmaster and was younger than many of the students. Further, he never had much patience with the semi-competent, and he was inclined to alienate the choirboys by making offensive remarks at rehearsals.

In August of 1705, there was an incident when Bach, upset with the poor performance of one of the church musicians, a certain J.H. Geyersbach, referred to him as a “zippel fagottist” (nanny-goat bassoonist). Later one evening, while Bach was walking with one of his cousins, Barbara Bach (elder sister of his future wife Maria Barbara), the same Geyersbach accosted him and demanded a retraction of the statement. When Bach would not apologize, the bassoonist attacked him with a walking stick. Bach drew his sword, but another student separated them. Bach complained to the Consistory (a clerical board responsible for matters pertaining to policies and personnel) that it would be unsafe for him to go about the streets if Geyersbach were not punished, and an inquiry was held. The Consistory informed Bach that he should not to have insulted Geyersbach and that he should try to live peaceably with the students. Furthermore, the Consistory complained that Bach was not adequately training the choirboys, and Bach responded that, as organist, he did not think that was part of his responsibility, since it was not part of his contractual duties.

Apparently dissatisfied with the Consistory’s handling of his complaint, Bach requested a leave of absence to visit Lübeck, the home of the brilliant organist Dietrich Buxtehude. Upon being granted four weeks, Bach walked to Lübeck, starting out around October 18th and covering the 250 mile distance in about ten days. When it came time to return to Arnstadt, Bach lingered in Lübeck for a full three months without consulting his employers. It is possible that Bach left Arnstadt intending to overstay his leave so that he might attend Buxtehude’s Abendmusiken, a series of special services for Advent of some renown in northern Germany. Perhaps, like Mattheson and Handel before him, he went to Lübeck primarily to see if there was any chance of succeeding the elderly Buxtehude in his prestigious post, and he was put off by the prospect of marrying Buxtehude’s 30-year-old spinster daughter. Apparently Bach did not like what he saw, for he returned to Arnstadt in February of 1706, and soon thereafter he married his cousin Maria Barbara. Upon Buxtehude’s death, two years later, his daughter remained unmarried.

On February 21, 1706, the Superintendent of the Consistory, Johann Gottfried Olearius, conducted a hearing into the matter of Bach’s extended absence. Bach defended himself by reminding the authorities that he had left his affairs in charge of a deputy, his cousin Johann Ernst Bach, and that he had not been paid during his absence. His replies were unsatisfactory to the council, and they next complained that his accompaniments to chorales were too elaborate for congregational singing and that he still refused to collaborate with the choirboys in producing cantatas. The council informed Bach that they could not provide a choir director to assume those responsibilities for him, and if he continued to refuse to work with the student choir, they would have to find someone more amenable. Bach repeated his demand that a choir director be hired, and he was ordered to apologize to the Consistory within eight days. There is no evidence that he ever apologized, and the Consistory dropped the matter for eight months. They brought it up again on November 11, and Bach undertook to answer them in writing. They also accused Bach of inviting a “stranger maiden” to make music in the church (possibly his cousin, Maria Barbara), but he had obtained the pastor’s permission in advance for this. Clearly, Bach’s relationship with his superiors was rapidly decaying, and he began to look for new employment elsewhere.

Neither Bach nor the Consistory took further action immediately. It is likely that Bach had returned from Lübeck with exalted ideas about church music, requiring facilities that the small town of Arnstadt could not provide. His ability was becoming known, and on November 28th, he was asked to examine a new organ at Langewiesen. Then, upon the death of Johann Georg Ahle in Mühlhausen on December 2nd, an attractive, vacant position offered Bach a way out of his increasing problems in Arnstadt.

Mühlhausen

(1707-1708)

When Bach was 22 years old, he arrived in Mühlhausen, a free city that had been governed for the previous 400 years by an elected council rather than by a royal court. This same council appointed Bach to the post of organist at the Blasiuskirche, a magnificent structure, dating from late Medieval times. For more than fifty years, the Blasiuskirche had previously employed the father and son, Rudolph and Georg Ahle, as organists. When the position became vacant after the death of the younger Ahle, Bach’s cousin, J.G. Walther, first applied and then withdrew an application for the post, moving instead to Weimar. By the time Bach submitted his application, the position had been vacant for six months, indicating that Bach was not the council’s first choice as Ahle’s successor. In spite of some reluctance on the part of the city council to hire a young man with a less than exemplary employment record, the salary settled upon the new organist was equal to what Bach had earned in Arnstadt, and it was considerably more than that of his predecessor.

During Georg Ahle’s tenure as organist, the musical standards of the church had decayed, but the post was still a respectable one, and several candidates played the organ at services as an audition for the post. Bach played on April 24, 1707 (Easter Sunday), and there may have been a performance that day of Cantata No.4, Christ Lag in Todesbanden. At the city council meeting on May 24th, no other name was considered, and on June 14th, Bach was interviewed, and an agreement was signed on June 15th. Soon afterwards, news of Bach’s new appointment reached Arnstadt, and his cousin, Johann Ernst Bach, and his predecessor, Börner, applied for the position at the Neuekirche on June 22nd and 23rd respectively. Bach formally resigned at Arnstadt on June 29th, and he moved to Mühlhausen a few days later. However, Bach could not foresee that his tenure in Mühlhausen would last for a scant nine-month period, due to the religious philosophical controversy raging in Mühlhausen between two religious factions: Pietist and Orthodox Lutherans.

On August 10, 1707, Tobias Lämmerhirt, Bach’s maternal uncle, died at Erfurt, bequeathing to his nephew a sum of 50 gulden. This inheritance was more than half of the composer’s annual salary, making it possible for Bach to propose and subsequently to marry his second cousin from Arnstadt, Maria Barbara Bach (b October 20, 1684), daughter of Johann Michael Bach and Catharina Wedemann. The wedding took place on October 17 in the village church at Dornheim, near Arnstadt. The presiding minister, J.L. Stauber (1660–1723), was a friend of the family, who himself married Regina Wedemann in June of 1708. Once he had established a household as a married man, Bach began to take on students as apprentices, and at least one student may have come to Bach during his years at Arnstadt. J.M. Schubart (1690–1721) studied with Bach from 1707 to 1717, and J.C. Vogler (1696–1763) arrived at the age of ten, left for a time, and returned from 1710 until 1715. These two students were later to be his immediate successors at Weimar, and from this time onwards in his career, Bach always had apprentices and was a demanding and meticulous teacher.

On February 4, 1708, the annual inauguration of the Mühlhausen City Council took place, and for this occasion, Bach was commissioned to compose a cantata. The council placed the best musicians of the city at his disposal, and for the first time, Bach had sufficient musical forces at hand to give him considerable liberty in composition. The resulting composition, now known as Cantata No.71, Gott ist mein König was then performed. It must have greatly impressed those in attendance, since the council had not only the libretto published, as was usual, but also the entire musical score. It remains the only cantata by Bach to have been published during his lifetime. Shortly thereafter, Bach submitted a plan for repairing and enlarging the organ at the Blasiuskirche. The council considered his plan on February 21st and decided to act upon it. About this time Bach played before the reigning Duke of Weimar, Wilhelm Ernst, who offered him a position at his court.

On June 25th, Bach wrote to the city council asking them to accept his resignation. Bach’s enthusiasm for his position at Mühlhausen was dampened by his dissatisfaction with the theological controversy that was ongoing in the city, since Mühlhausen was a center of Lutheran Pietism. While there is some evidence that Bach was drawn to the more devotional style of worship advocated by the Pietists, he could not have rested comfortably with their attitude of indifference toward the liturgical arts. It did not take long for Bach to realize that Pietism was moving toward an aesthetic like that of the Calvinists, in which artistic, technically demanding music was viewed as a detriment to pure worship. Pietists were increasingly uncomfortable with music more complex than unadorned motets and musically simple hymns. Pastor Johann A. Frohne of the Blasiuskirche was a Pietist, but there no evidence to suggest that he and Bach did not get along well. However, the people of his congregation did not like Bach’s music, and their treatment of him and his new bride was less than warm. Bach developed a close acquaintance with Pastor Georg Christian Eilmar of the Marienkirche in Mühlhausen, who for a decade before Bach’s arrival, had defended Orthodox Lutheranism in the ongoing debate with Pietism. Pastor Eilmar supplied the texts for some of Bach’s cantatas from this period. Eilmar and his family stood as godparents for Bach’s firstborn daughter and son.

Undoubtedly, the larger salary offered at Weimar was highly attractive to Bach, but it is clear, even from his tactful letter to the city council, who had always treated him well, that there were other reasons for his desire to leave. Bach stated that he had come to Mühlhausen in order to compose a body of “well-appointed church music,” and that given his present circumstances, he perceived the attainment of that goal to be impossible, and he had decided to leave in order that he might achieve his goal elsewhere. He also said that he had encouraged such music, not only in his own church, but also in the surrounding villages, where the harmony was often “better than that cultivated here.” Bach had also gone to some expense to collect “the choicest sacred music.” But in all these endeavors, members of his own congregation had consistently opposed him, and their attitude, stemming from their Pietistic viewpoint, was not likely to change.

The city council reluctantly accepted his resignation on June 26th and let him go, asking him only to supervise the organ building at the Blasiuskirche. No matter how poor Bach’s relationship with his congregation may have been, he remained on good terms with the city council. They paid him to return and perform a cantata at the council inauguration service in 1709, using the refurbished organ, but all traces of this work have been lost. Much later, in 1735, he negotiated on friendly terms with the city council on behalf of his son, Johann Gottfried Bernhard who was thereafter employed in the city.

Weimer

(1708-1717)

From Mühlhausen, Sebastian Bach and his wife moved approximately 40 miles north to Weimar to begin a very productive period in his career. Previously, in his letter of resignation at Mühlhausen, Bach stated that he had been appointed to Duke Wilhelm Ernst’s “Capelle und Kammermusik.” And due to this statement, it was long thought that Bach did not officially become court organist at Weimar for some time after his arrival. However, surviving court documents plainly show that on July 14, 1708, when his first salary payment was made, he was called “the newly appointed court organist,” and he was always referred to in this manner until March 1714, when he became Konzertmeister as well upon the retirement of Effler. Actually, this was Bach’s second stay in Weimar, since in 1703, he had been previously employed at the court for a few months as violinist.

Bach composed many of his famous organ works at Weimar, and Duke Wilhelm Ernst took great pleasure in his playing. For his labors, Duke Wilhelm paid Bach handsomely: from the beginning, his salary was twice the amount he had received in Mühlhausen, and it was larger than that of his predecessor, Effler (150 florins, plus some allowances). His salary was increased to 200 florins in 1711, to 215 florins from June 1713, and to 250 florins on his promotion in 1714. On March 20, 1715, Duke Wilhelm ordered that his share of casual fees was to be the same as that of the Kapellmeister. Even with his many duties, Bach still enjoyed a considerable amount of free time, evidenced by his cultivation of a friendship with Telemann who was then working in Eisenach from 1708-1712. Together with the violinist, Pisendel, Bach copied a Concerto in G Major by Telemann during Pisendel’s visit to Weimar in 1709.

At Weimar, Bach’s family increased as six of his children were born there: Catharina, baptized December 29, 1708; Wilhelm Friedemann, born November 22, 1710; unnamed twins, born February 23, 1713, who died within a few days; Carl Philipp Emanuel, born March 8, 1714; and Johann Gottfried Bernhard, born May 11, 1715. The godparents of these children, coming from many different locations, demonstrate that Bach and his wife maintained contact with friends and relatives from Ohrdruf, Arnstadt, and Mühlhausen, as well as establishing new friendships in Weimar. As evidence of Bach’s close friendship with Telemann, the composer stood as godfather at the baptism of Carl Philipp Emanuel along with Adam Weldig. In March of 1709, it is known that Bach and his wife, along with one of her sisters, were living with Adam Immanuel Weldig, a falsettist and Master of the Pages. They probably stayed in Weldig’s house until August of 1713, when Weldig moved to Weissenfels. The location of the Bach family residence in Weimar is not known before or after these dates.

Bach’s previously mentioned cousin, Johann Gottfried Walther, had been the organist at the Stadtkirche in Weimar since July of 1707. Walther was related to Bach through his mother, a Lämmerhirt, and the cousins remained lifelong friends. In September of 1712, Bach stood as godfather to Walther’s son, and later in 1735, Bach negotiated on Walther’s behalf with the Leipzig publisher J.G. Krügner. Furthermore, as evidence of their close bond, during his nine years at Weimar, Bach gave Walther some 200 pieces of music: some by Buxtehude and many other compositions of his own.

Regarding Bach’s students, Schubart and Vogler have already been mentioned. The student for whom Bach was paid by Duke Ernst August’s account in 1711-12 was not the Duke himself, but he was a page in the Duke’s employ, named Jagemann. J.G. Ziegler (1688-1747) matriculated at the University of Halle in October of 1712, but before that time he had studied with Bach for about two years, and he had been taught to play chorales “not just superficially, but according to the sense of the words.” Bach’s wife stood as godmother to Ziegler’s daughter in 1718, and in 1727 Bach employed him as his agent in Halle, for the publication of Partitas Nos. 2 and 3. P.D. Krauter of Augsburg (1690-1741) studied with Bach in Weimar from March 1712 until September 1713. Johann Lorenz Bach, his cousin, arrived in the autumn of 1713, and he concluded his studies by July of 1717. Johann Tobias Krebs (1690-1762) studied first with Johann Gottfried Walther from 1710, and subsequently with Bach from 1714 until 1717. Johann Bernhard Bach, his nephew, studied with J.S. Bach from some time in 1715 until March of 1719, alongside Samuel Gmelin (1695-1752), who appears to have left Weimar in 1717.

Bach was the overseer of extensive renovations to the organ in the castle chapel in 1713 and 1714. The organ was originally built by Compenius in 1658. It was overhauled in 1707, and a Sub-Bass was added by J.C. Weishaupt who carried out additional maintenance work in 1712. Further alterations were done beginning in June of 1712 by H.N. Trebs (1678-1748), who had moved from Mühlhausen to Weimar in 1709. Bach and Trebs had worked together on a new organ at Taubach in 1709, and in 1711 Bach wrote a testimonial for Trebs’s work. In 1713 Bach and J.G. Walther became godfathers to Trebs’s son. Bach and Trebs collaborated again in 1742, with an organ at Bad Berka. Trebs’s new organ at Weimar was completed in 1714, but the details of his work are unknown, except that the Duke was determined to have the instrument include a Glockenspiel. Great trouble was taken over obtaining bells from dealers in Nuremberg and Leipzig. The original set of 29 bells (an odd number) had to be replaced because of difficulties with their blend and pitch.

In December of 1709 and February of 1710 Bach was paid for repairing harpsichords in the household of the junior Duke of Saxe-Weimar, Ernst August and Prince Johann Ernst. On January 17, 1711, he was godfather to a daughter of J.C. Becker, a local burgher. In February of 1711, Prince Johann Ernst went to the University of Utrecht. From February 21, 1713, Bach was lodged in the castle at Weissenfels. Duke Christian’s birthday fell on February 23rd, and it is now known that Cantata No.208, Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd (the “Hunting Cantata”), was performed. This was Bach’s first cantata to employ recitatives and arias of the new Italianate style. In this score Bach contradicted sharps by flats, rather than by using naturals, an old-fashioned habit that he progressively abandoned during 1714.

In May of 1713, Prince Johann Ernst returned from Utrecht with a large collection of musical scores. The previous February he had been in Amsterdam, and he may have met the blind organist J.J. de Graff, who was in the habit of playing recent Italian concertos as keyboard solos. This may have given rise to the numerous concerto arrangements made by Bach. He created various organ transcriptions of the Italian material, and particularly Vivaldi’s 1712 collection of concerti, L’Estro armonico, had a profound influence on his style of composition. This was in fact a decisive moment in Bach’s development: from that point he combined his earlier counterpoint style, with its northern German and French influences, with Vivaldi-like harmonic planning and thematic development. About this time, Bach established a professional relationship with castle librarian, Salomo Franck, an exceptionally talented poet, who wrote well-crafted free verse which Bach would set to music in several of his future Cantatas. In the four years remaining in Weimar, Bach completed the bulk of his organ works, including the Orgelbüchlein, and many of his harpsichord compositions. He also composed several chamber and orchestral works, including his six Brandenburg Concerti.

In 1713, Bach applied to succeed Handel’s teacher Zachau (who had died in 1702) in Halle, where a large new organ was being built, a three-manual instrument of 65 stops. The authorities of Halle’s Liebfrauenkirche naturally wanted such a famous a musician to play its new instrument, and they offered Bach the position. Bach tentatively accepted the job. After his return to Weimar, Bach notified the Duke that he had entered into negotiations with Halle. Bach may have been involved directly in planning the enlargement of the organ, when Zachow became incapacitated, for it is certain that he stayed in Halle from November 28th to December 15th at the church authorities’ expense. However, when the authorities in Halle finally submitted the offer formally, they had added several negative stipulations which were not previously known to Bach: in addition to a cut in salary and heavier responsibilities, which included performances practically every day of the week, the new organist was to be prevented from moonlighting and required to write a cantata once a month. The final stipulation, that the chorales be accompanied “on the diapason with two or three other stops of soft quality, changing the stops for each verse, but never using the reeds or mixtures,” was insulting to an organist of Bach’s stature, and he promptly refused the offer. The jilted Halle authorities wrote to Bach’s employer to suggest that the reason he had entered into negotiations with them was to extort a higher salary from the Duke. Bach fired off an angry letter, informing the city of Halle that the salary it had offered was lower than that already being paid to him by Duke Wilhelm Ernst. Shortly thereafter the Duke doubled Bach’s salary as a means of keeping him in Weimar, and Bach was given the new additional designation as Konzertmeister, ranking after the Vice-Kapellmeister. Bach remained on good terms with Halle thereafter, and he was employed there as an organ examiner in 1716. Gottfried Kirchhoff was appointed organist in Halle in July of 1714.

In 1714, Bach improvised for Prince Friedrich in the royal chapel at Cassel. The prince was so pleased that he withdrew a ring from his finger and presented it to the organist. Later that year Bach visited Leipzig, the city where he was destined to spend the last 27 years of his life. The purpose of this visit was to become acquainted with Johann Kuhnau, and Bach took advantage of the occasion by composing Cantata, No.61, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, which he performed there. Back in Weimar, on Palm Sunday, March 25, 1714, Bach performed Cantata No.182, Himmelskönig, sei willkommen. This was shortly after his appointment as Konzertmeister, and he was responsible for writing a cantata every four weeks. Although he had hoped to complete an annual cycle of cantatas in four years, his compositional plan was not to be realized in Weimar. On August 1, 1715, the musically gifted Prince Johann Ernst died, causing Bach the loss of a valued ally and plunging the Duchy of Weimar into mourning from August to November of 1715, when not a note of music was allowed. From 1717, there are no extant cantatas at all.

On April 4, 1716, Bach, like the librettist Salomo Franck and “the book-printer,” was paid for “Carmina,” bound in green taffeta, that had been presented on some unspecified occasion, perhaps on January 24th when Duke Ernst August had married Eleonore, sister of the Prince of Cöthen. Duke Ernst’s birthday was celebrated in April, and two horn players from Weissenfels came to Weimar, possibly brought over for a repeat performance of Cantata No.208. Meanwhile, the new organ at Halle had been making progress, and on April 17th, the council decided that Bach, Kuhnau of Leipzig, and Rolle of Quedlinburg should be invited to examine it on April 29th. They all accepted, and each received remuneration of 16 thalers, plus food and traveling expenses. The examination began at 7:00 A.M., and it lasted for three days, until some time on May 1st, when the experts wrote their report, a sermon was preached, and fine music was performed. On May 2, the organist and the three examiners met the builder to discuss details, and the council gave a tremendous banquet in honor of the organ’s completion.

In July of 1716, Bach and an Arnstadt organ builder signed a testimonial for J.G. Schröter, who had built an organ at Erfurt. In 1717, Bach was mentioned in print for the first time: in the preface to Mattheson’s Das beschützte Orchestre, dated February 21st, in which Mattheson referred to Bach as “the famous Weimar organist” saying that his works, both for the church and for keyboard, led one to rate him highly, and asked for biographical information.

The factors that led to Bach’s departure from Weimar are complex and varied. In 1703, he had been employed by Duke Johann Ernst, and since his return in 1708, by Duke Wilhelm, Johann’s elder brother. The brothers had been on bad terms for years, and when Johann Ernst died in 1707 and his son Ernst came of age in 1709, things became no better. For a long time, the disagreements between the two reigning Dukes of Saxe-Weimar did not affect Bach in any negative way. Perhaps Ernst’s younger half-brother (Johann, the composer) may have had some positive influence in the disputes. But the latter died in 1715, and the “court difficulties” worsened. Bach, like the rest of Wilhelm’s household, was thereafter forbidden to associate with Ernst in any manner. The musicians, though paid by both households, were threatened with fines of 10 thalers if they served Ernst in any way.

No extant Bach cantata can be securely dated between late January and early December 1716. It may be that Bach expressed his disapproval of Duke Wilhelm’s behavior toward the junior Duke by evading his own responsibilities. However, Bach did not openly disapprove of the Duke Wilhelm until he discovered that a new Kapellmeister was being sought elsewhere. Drese senior died on December 1, 1716, and his son, the Vice-Kapellmeister, was by all accounts a nearly incompetent musician. Bach produced Cantata No.70a, Wachet, betet, seid bereit, (now lost) for December 6, Cantata No.186a, Ärgre dich, o Seele, nicht, (now lost) for December 13, and Cantata No.147a, Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben, (now lost) for December 20 (three successive weeks). However, there were no more such works after these. By Christmas, Bach may have found out that the Duke was negotiating to have Telemann as the new Kapellmeister. But these negotiations came to nothing. However, since Bach felt somewhat insulted by these negotiations, he became determined to find a new position elsewhere as Kapellmeister. He was offered one by Prince Leopold of Cöthen, brother-in-law to Duke Ernst (Bach and the prince had probably met at Ernst’s wedding in January of 1716), and the appointment was confirmed on August 5, 1717. No doubt Bach then asked Duke Wilhelm’s permission to leave Weimar, and no doubt he was refused, since Duke Wilhelm was very annoyed that his nephew had obviously had a hand in finding Bach a position that carried more prestige and a higher salary as well.

Duke Wilhelm and Bach must have remained on speaking terms for the time being, for at some point near the end of September, Bach was in Dresden and free to challenge the French keyboard virtuoso Louis Marchand to a contest. Versions of this affair differ, but according to Birnbaum (who wrote in 1739, probably under Bach’s supervision), Bach “found himself” at Dresden and was not sent for by “special coach.” Once there, some court official persuaded him to challenge Marchand to a contest at the harpsichord. The idea that they were to compete at the organ is a posthumous account of this story. Whatever the truth may be, it is universally agreed that Marchand suddenly left Dresden without the contest ever having taken place.

In late October of 1717, Duke Wilhelm set up an endowment for his court musicians, and the second centenary of the Reformation was celebrated from October 31st to November 2nd. Presumably Bach took part in these ceremonies, though there is no evidence that he set any of the librettos that Franck had provided for this occasion. Emboldened by the Marchand affair the previous month, Bach demanded his release in such terms that Duke Wilhelm had him imprisoned from November 6th until his dismissal on December 2nd. The court at Cöthen had paid Bach 50 thalers on August 7th. Some have supposed that this was for traveling expenses and that Bach had his wife and family moved to Cöthen soon afterwards. However, it is unlikely that the Duke Wilhelm would have allowed the Bachs to move until he had agreed to allow Bach to leave his position in Weimar on December 2nd. The younger Drese became Kapellmeister in his father’s place, and Bach’s pupil J.M. Schubart became court organist. The post of Konzertmeister simply ceased to exist after Bach’s departure.

Cothen

(1717-1723)

Bach’s relationship with his new employer, Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, was not only a professional relationship, but also one of genuine friendship between the composer and the 23-year-old prince, a man who was described by Bach himself as a person who loved and understood music. Prince Leopold was born in 1694 of a Calvinist father and a Lutheran mother. The father died in 1704, and the mother ruled as regent until Leopold came of age in December of 1715. Previously, in October of 1707, Leopold persuaded his mother to take on three musicians, and he gradually founded a court orchestra at Cöthen over a period of several years, at great expense to the court. While studying in Berlin in 1708, he met A.R. Stricker. From 1710 to 1713, he was on the usual grand tour, during which he studied music with J.D. Heinichen in Rome. Prince Leopold returned capable of singing bass, and of playing the violin, the viola da gamba, and the harpsichord. The Berlin court orchestra had broken up in 1713, and from July of 1714, Prince Leopold employed Stricker as Kapellmeister and his wife as a soprano and lutenist. By 1716, 18 musicians were employed at the court. In August of 1717, Stricker and his wife resigned from their positions, leaving Prince Leopold free to appoint Bach as his new Kapellmeister .

At Cöthen, the Saint Jakob organ was in poor condition. The court chapel was Calvinist, and therefore no elaborate music was performed. Bach’s duties did not include those as court organist, and the two-manual organ had only 13 or 14 stops. The Lutheran Church of Saint Agnus had a two-manual organ of some 27 stops. There is no doubt that Bach used one or both of these organs for teaching and private practice. He took communion at Saint Agnus Church, and he took part in the baptisms at the court chapel. But he had no official responsibilities in either church. He may have been involved in an event in May of 1719, when a cantata was performed for the dedication festival of Saint Agnus. The printer’s bill for one thaler and eight groschen was endorsed by the pastor: “The church wardens can give him 16 groschen; if he wants more, he must go to those who gave the order.”

Bach’s basic salary of 400 thalers was twice the amount that Stricker had been paid, and extra allowances made it up to about 450 thalers. Only one court official was paid more. There is other evidence that Bach was held in high esteem: on November 17, 1718, the last of his children by his first wife (who died in infancy) was named after Prince Leopold, who himself was the child’s godfather. Bach’s residence in Cöthen is not definitely known, but it seems likely that he began as a tenant at 11 Stiftstrasse. In 1721, when that house was bought by the prince’s mother for the use of the Lutheran pastor, he moved to 10 Holzmarkt. The orchestra needed a room for their weekly rehearsals, and Prince Leopold supplied it by paying rent to Bach (12 thalers a year from December 1717 to 1722). Presumably there was a suitable room in Bach’s first house. Whether he continued to use that room after his move in 1721, and why he was not paid rent after 1722 is not clear.

The date of the first rent payment suggests that Bach and his household moved to Cöthen within two days of his release from prison in Weimar in early December. After hasty rehearsals, he helped to celebrate Prince Leopold’s birthday on December 10th. The court accounts suggest that Bach was expected to compose a work annually for Prince’s birthday. Among the most famous of these “tribute cantatas” was Cantata No.66a, Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen, written in 1718. In 1721 there may have been no birthday celebration, since Prince Leopold was married, at Bernburg the next day. Cantata No.173a, Durchlauchtster Leopold, was undoubtedly a birthday work for the Prince, but the exact year in which Bach composed this work is not known. Cantata No. 36a, Steigt freudig in die Luft, was performed at Cöthen on November 30, 1726, for the birthday of Prince Leopold’s second wife.

The decidedly secular nature of these several “birthday cantatas” along with those composed for the New Year as well, show that Bach had limited use of singers at Cöthen, since most of these cantatas contain primarily recitatives, arias, and duets, with few choruses. Undaunted by these limitations, Bach honed his skills in writing da capo arias, and he produced beautiful solos and vocal duets that were technically demanding and of considerable length and complexity. While specific works cannot be associated with precise dates in many instances, it is widely accepted that several of Bach’s earliest works performed later in Leipzig were arrangements of his secular cantatas first performed in Cöthen, adapted to religious texts.

On May 9, 1718, Prince Leopold went to drink the waters at Carlsbad for about five weeks, taking with him his harpsichord, Bach, and five other musicians. Early in 1719, Bach was in Berlin negotiating for a new harpsichord. About this time he was busy composing, since between July of 1719 and May of 1720, 26 thalers were spent on bindings. During 1719, Handel visited his mother at Halle, only 19 miles away. It is believed that Bach tried but failed to make contact with Handel. Bach also disregarded a renewed request from Mattheson for biographical material.

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was nine years old in 1719, and the title page of his Clavier-Büchlein is dated January 22, 1720. In May of that year, Bach again went to Carlsbad with Prince Leopold. It is not known when they returned, but it was after July 7th, since that was the date of Maria Barbara’s funeral. There is no reason to doubt Emanuel’s story that his father returned to find her dead and already buried. His wife had been nearly 36. Her death may well have shaken Bach to the core, and it may have even led him to consider returning to the service of the church again. However, there was a more practical reason for his taking an interest in Saint Jacobi Church at Hamburg: the death of the organist, Heinrich Friese, in September of 1720. Bach had known Hamburg in his youth, and he must have viewed the vacant position as an attractive one, since the Schnitger organ in Hamburg was a four-manual instrument with some 60 stops. There is no evidence that Bach was ever invited to apply for the position, but he may well have made inquiries on his own.

Whatever the particulars were, his name was one of eight being considered on November 21st, and Bach was in Hamburg at about that time. A competition was arranged for November 28th, but Bach had had to leave for Cöthen a few days before then. Three candidates did not appear, and the judges were not satisfied with the other four. An approach was made to Bach, and the committee met twice to consider him for the position, but Bach eventually refused the post. His reasons for doing so remain unknown, but it is supposed that they were of a financial nature, since the approved candidate was expected to make a substantial contribution to the church’s funds.

From the way in which the committee kept the post open for Bach, one may suppose that they had heard his recital at Saint Katharinen. Bach played before the aged Reincken, the magistracy and other notables; that he played for more than two hours in all; and that he extemporized in different styles on the chorale An Wasserflüssen Babylon for almost half an hour, just as the better Hamburg organists had been accustomed to doing at Saturday Vespers. As a fantasia on this chorale was one of Reincken’s major works, this may seem a tactless choice, but the chorale was chosen by “those present” and not by Bach himself. Reincken is reported to have said, “I thought this art was dead, but I see it still lives in you,” and showed Bach much courtesy.

During 1720, Bach made copies of the works for unaccompanied violin, he and must have been preparing the Brandenburg Concertos, whose autograph full score was dedicated on March 24, 1721, to the Margrave Christian Ludwig before whom Bach had played in Berlin while negotiating for the new Cöthen harpsichord. What he played is not known, but he was invited to send in some compositions. As he himself said, he took “a couple of years” over this commission, and then he submitted six works written to exploit the resources of Cöthen. Such resources do not seem to have been available to the Margrave of Brandenburg, and it is not really surprising that he did not thank Bach, send a fee, or ever use the scores.

On June 15, 1721, Bach was the 65th communicant at Saint Agnus Church, and one “Mar. Magd. Wilken” was the 14th. This may well have been Bach’s future wife – the mistake in the first name is an easy one – but Anna Magdalena makes no formal appearance until September 25th, when Bach and she were the first two among the five godparents of a child called Hahn. This baptism is recorded in three registers. In two of them Anna Magdalena is described as a “court singer,” and in the third, simply as a “chamber musician.” In September, Anna was again a godmother to a child called Palmarius, and again the registers differ in describing her occupation. Her name does not appear in court documents until the summer of 1722, when she is referred to as the Kapellmeister’s wife. Her salary, which was half Bach’s, is noted as paid for May and June 1722.

Practically nothing is known of Anna Magdalena’s early years. She was born on September 22, 1701, at Zeitz. Her father, Johann Caspar Wilcke, was a court trumpeter who worked at Zeitz until about February 1718, when he moved to Weissenfels where he died at the end of November in 1731. The surname was variously spelled. Anna’s mother, Margaretha Elisabeth Liebe, who died in March of 1746, was the daughter of an organist and sister of J.S. Liebe who, besides being a trumpeter, was the organist of two churches at Zeitz from 1694 until his death in 1742. As a trumpeter’s daughter, Anna may well have met the Bachs socially. However, she was paid for singing, with her father, in the chapel at Zerbst on some occasion between Easter and midsummer of 1721. By September, at age 20, she was at Cöthen, well acquainted with Bach (age 36), and ready to marry him on December 3rd. Prince Leopold gave Bach permission to be married in his own lodgings. At about this time Bach paid two visits to the city wine cellars, where he bought first one firkin of Rhine wine, and later two firkins, all at a cut price, 27 instead of 32 groschen per gallon.

On December 11, 1721, Prince Leopold married his cousin Friderica, Princess of Anhalt-Bernburg. The marriage was followed by five weeks of illuminations and other entertainments at Cöthen. This was not however an auspicious event for Bach: he was to leave Cöthen partly because the princess was “eine Amusa” (someone not interested in the Muses), and she broke up the happy relationship between Bach and her husband. Perhaps her unfortunate influence had made itself felt even before she was married to Bach’s employer and friend.

A legacy from Tobias Lämmerhirt, Bach’s maternal uncle, had facilitated his first marriage. When Tobias’s widow died in Erfurt in September of 1721, Bach received something from her will, too. However, it was not in time for his second marriage. In January of 1722, Bach’s sister Maria, together with one of the Lämmerhirts, challenged the will, saying that Bach and his brothers Jacob (in Sweden) and Christoph (at Ohrdruf) agreed with them (Christoph had died in 1721). Bach heard of this only by accident, and in mid March, he wrote to the Erfurt council on behalf of Jacob as well as himself. He objected to his sister’s action and said that he and his absent brother desired no more than was due to them under the will. On April 16, Jacob died, and the matter seems to have been settled by the end of the year. Bach’s legacy must have amounted to rather more than a year’s pay.

In the summer of 1722, there was no Kapellmeister at the court of Anhalt-Zerbst, and Bach was commissioned to write a birthday cantata for Prince Leopold. For this commission, he was paid 10 thalers in April and May. The birthday was in August, and the payments made during that month presumably refer to the performance of the cantata. This work, which is now lost, was scored for two oboes d’amore and “other instruments.”

Several didactic works for keyboard belong to the Cöthen period. One is the Clavierbüchlein for Anna Magdalena Bach. Twenty-five leaves are extant, but comprise only a third of size of the original manuscript. There is a title page on which Anna Magdalena wrote the title and the date, and Bach noted the titles of three theological books. Bach first gave the notebook to his wife early in 1722, and it seems to have been filled by 1725. The autograph of Das Wohltemperirte Clavier (Book I) is dated 1722 on the title page, but 1732 at the end. The writing is uniform in style, and for various reasons it is incredible that he did not finish the manuscript until 1732. The final version was preceded by drafts, like those in W.F. Bach’s Clavier-Büchlein, begun in 1720. Presumably Bach brought them together for convenience, partly to serve as the last step in his keyboard course, partly to exhibit the advantages of equal temperament. Bach transposed some of the pieces to fill gaps in his key scheme: the odd pairing of the Prelude in six flats with the Fugue in six sharps suggests that the former was originally in E minor, the latter in D minor.

The title page was almost certainly the only part of the Orgel-Büchlein that Bach wrote while at Cöthen, but as another educational work, it is best mentioned here. It was meant to be a collection of Chorale Preludes, not only for the seasons of the church year, but also for occasions when such subjects as the Lord’s Prayer, or Penitence, were being emphasized. A few items date from about 1740. In the rest, the writing resembles that of the Cantatas of 1715-1716. Of the 164 preludes Bach allowed for, he completed fewer than 50. Last in this group of works come the Inventions and the Sinfonias, the autograph copy of which is dated “Cöthen, 1723.” Many of these short works had already appeared in earlier versions and under different titles in W.F. Bach’s Clavier-Büchlein of 1720.

The story of Bach’s move to Leipzig begins with the death of Johann Kuhnau, Kantor of the Thomasschule, in June of 1722. Six men applied for the position, among them Telemann, who was still remembered for the good work he had done at Leipzig 20 years earlier. He had been doing a similar job at Hamburg for about a year, and he was probably the most famous German musician actually living in Germany at the time. One of the Kantor’s duties was to teach Latin. Telemann refused to do that. Nevertheless, he was appointed to the position in Leipzig on August 13th. However, the Hamburg authorities would not release him, and they offered to increase his salary if he would stay. Therefore, in November Telemann declined the Leipzig post. At a meeting on November 23rd, Councillor Platz said that Telemann was no loss and that what was needed was a Kantor to teach other subjects besides music. Of the remaining five candidates, three were invited to give trial performances. Two of the candidates dropped out, one because he refused to teach Latin at the school. By December 21st, two additional Kapellmeisters had applied: Bach and Graupner. The other candidates were Kauffmann of Merseburg, Schott of the Leipzig Neukirche, and Rolle of Magdeburg.Of the five candidates, Graupner was preferred, since he was a reputable musician who had studied at the Thomasschule. He successfully performed his test of two cantatas on January 17, 1723. But in March, he too withdrew, having been offered a higher salary at Darmstadt. On February 7, 1723, Bach performed his test pieces: Cantata No.22, Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe and the masterfully composed Cantata No.23, Du Wahrer Gott und Davids sohn. Rolle and Schott had also been heard, and possibly Kauffmann too. The Princess of Cöthen died on April 4th, but it was too late to affect Bach’s decision. On April 9th, the council considered Bach, Kauffmann and Schott. Like Telemann, none of them wished to teach Latin. Councillor Platz said that since the best men could not be hired, they must make do with the mediocre. The council evidently resolved to approach Bach, for on April 13th, he obtained written permission to leave Cöthen. On April 19th, he signed a curious document that reads as if he were not yet free from Cöthen, but he could be free within a month, and he also said he was willing to pay a deputy to teach Latin. On April 22nd, the council agreed on Bach, one of them hoping that his music would not be too “theatrical.” On May 5th, Bach came in person to sign an agreement, and on May 8th and 13th, he was interviewed and sworn in by the ecclesiastical authority. On May 15th, the first installment of his salary was paid, and on May 16th, he “took up his duties” at the university church, possibly with a performance of Cantata No.59, Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten. With his family and their belongings, Bach moved to Leipzig for good on May 22nd, and a week later, he performed Cantata No.75, Der Elenden sollen essen at the Nikolaikirche on May 30th. On June 1st at 8.30 A.M., he was formally presented to the school.

This story has been told in some detail, because it sheds light on the circumstances in which Bach worked at Leipzig. To him, the Kantorate was a step downwards on the social ladder, and he had little respect for his employers. To the council, Bach was a third-rater, a mediocrity, who would not do what they expected a Kantor to do, i.e., teach Latin to the school boys, as well as organize the city’s church music. The stage was set for trouble, and in due course trouble came to Bach. Councillor Platz on Telemann is curiously echoed by Councillor Stieglitz, ten days after Bach’s death: “The school needs a Kantor, not a Kapellmeister; though certainly he ought to understand music.“

Leipzig

(1723-1750)

The position of Kantor at the Saint Thomas School, held conjointly with that of Civic Director of Music, had been associated with a wealth of tradition since the 16th century. It was one of the most notable positions in German musical life, and there can be little doubt that the general attractiveness of the position in itself played a part (very likely the decisive part) in Bach’s decision to move from Cöthen to Leipzig. His subsequent remark about the social step down from Kapellmeister to Kantor must be seen in the context of his later disagreements with the Leipzig authorities, as indeed his letter to Erdmann, a friend of his youth, on October 28, 1730, makes very clear. However, Bach was not the only Kapellmeister to apply for the Leipzig post. The duties were incomparably more varied and demanding than those in Cöthen or Weimar had been, and they more or less corresponded to those undertaken by Telemann in Hamburg. It cannot have been mere chance that Bach wanted to tackle a range of duties comparable with those of his friend. Above all, he must have preferred the greater economic and political stability of a commercial metropolis governed democratically to the uncertainties of court life, ruled by an absolute prince. Leipzig University was the foremost educational institution in the German-speaking world at the time, and this also must have been another special attraction in the eyes of a father whose sons would need such education.

The “Cantor zu St. Thomae et Director Musices Lipsiensis” was the most important musician in Leipzig. In this position, Bach was primarily responsible for the music of the four principal Leipzig churches: the Thomaskirche, the Nikolaikirche, the Matthäeikirche (or Neukirche), and the Petrikirche. His additional duties included other aspects of the town’s musical life as well, and these were controlled by the town council. In carrying out his duties, he could call on the pupils of the Thomasschule, the boarding-school attached to the Thomaskirche, whose musical training was his responsibility, as well as the town’s professional musicians. Normally the pupils, about 50 to 60 in number, were split up into four choir classes (Kantoreien) for the four churches. The requirements would vary from class to class: polyphonic music was required for the Thomaskirche, Nikolaikirche (the civic church), and the Matthäeikirche, with figural music only in the first two. At the Petrikirche only monodic chants were sung. The first choir class, with the best 12 to 16 singers, was directed by the Kantor himself, and the choir sang alternately in the two principal churches, the Nikolaikirche and Thomaskirche. The other classes were in the charge of prefects, appointed by Bach, who would be the older, more experienced pupils of the Thomasschule.

Musical aptitude was a decisive factor in the selection of pupils for the Thomasschule, and it was Bach’s responsibility to assess and train them through daily choir practice. There was also instrumental instruction for the most able students, which Bach had to provide free of charge. By this method, he was able to make good any shortage of instrumentalists for his performances, since the number of professional musicians employed by the town (four Stadtpfeifer, three violinists, and one apprentice) was held throughout his period of office at the same level as it had been during the 17th century. For further instrumentalists, Bach drew on the university students. In general the age of the Thomasschule pupils ranged between 12 and 23. Remembering that voices then broke around the age of 15-16, it is clear that Bach could count on solo trebles and altos who already had at least five years of daily practical experience as choristers.

As far as church music was concerned, Bach’s duties centered on the principal services on Sundays and church festivals, as well as some of the more important secondary services, especially Vespers. In addition, he could be asked for music for weddings and funerals, for which he would receive a special fee. Such additional income was important to Bach, as his salary as Kantor of the Thomaskirche and director of music came to only 87 thalers and 12 groschen (besides allowances for wood and candles, and payments in kind, such as corn and wine). In fact, including payments from endowments and bequests as well as additional income, Bach received annually more than 700 thalers. Further, he had the use of a spacious official residence in the south wing of the Thomasschule, which had been renovated at a cost of more than 100 thalers before he occupied it in 1723. Inside the Kantor’s residence was the so-called Komponirstube (composing room), his professional office, containing his personal music library and the school’s. The buildings of the old Thomasschule were demolished in 1903 to make room for what is now the senior minister’s quarters. It was also then that the west façade of the Thomaskirche was rebuilt in its present neo-Gothic style.

During his early Leipzig years, Bach involved himself in church music with particular thoroughness and extreme energy. This activity centered on the Hauptmusic composed for Sundays and Church-Year festivals. The performance of a polyphonic cantata, with a text related as a rule to the Gospel for the day, was a long-standing tradition for Leipzig’s Kantor. Even so, Bach engaged on a musical enterprise without parallel in the city’s musical history: in a relatively short time he composed five complete cycles of cantatas for the Church-Year, with about 60 cantatas in each cycle, creating a repertory of roughly 300 sacred cantatas. The first two cycles were prepared immediately, for 1723-1724 and 1724-1725. The third cycle took longer to complete, being composed between 1725 and 1727. The fourth cantata cycle, to texts by Picander, appears to date from 1728-1729, while the fifth cycle again occupied a longer period, possibly extending into the 1740s. The established chronology of Bach’s vocal works makes it clear that the main body of the cantatas was in existence by 1729 and that Bach’s development of the cantata was effectively complete by 1735. The existence of the fourth and fifth cycles has been questioned because of the fragmentary form in which they survive, compared with the almost complete survival of the first, second, and third cycles. However, until proof of their non-existence can be offered, the number of five cantata cycles, as laid down by C.P.E. Bach in his father’s obituary of 1754, must continue to stand.

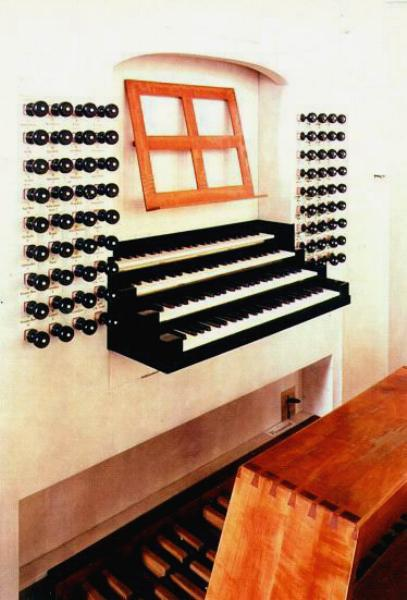

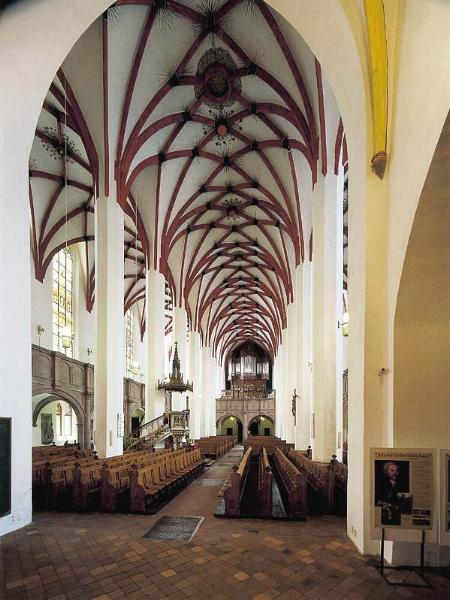

The first cantata cycle began on the first Sunday after Trinity in 1723 with Cantata No.75, Der Elenden sollen essen which was performed “mit gutem applausu” at the Nikolaikirche, followed by Cantata No.76, Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes for the second Sunday after Trinity, performed at the Thomaskirche. The two largest churches in Leipzig are both Gothic in style, and in Bach’s time they contained stone and wooden galleries. The choir lofts were on the west wall of the nave above the council gallery. The organs were also in the choir lofts (the Schüler-Chor): the Nikolaikirche and the Thomaskirche each had a three-manual organ with 36 and 35 stops respectively (Oberwerk, Brustwerk, Rückpositiv, Pedal). The Thomaskirche had a second organ, fitted to the east wall as a “swallow’s nest,” with 21 stops (Oberwerk, Brustwerk, Rückpositiv, Pedal). However, this instrument fell into dilapidation and was demolished in 1740. The organs were always played at cantata performances, during which they would provide continuo accompaniment. They were played by the respective organists at each church. During Bach’s term of office, these organists were Christian Heinrich Gräbner (at the Thomaskirche until 1729), J.G. Görner (at the Nikolaikirche until 1729, then at the Thomaskirche), and Johann Schneider (at the Nikolaikirche from 1729). Bach himself, who had not held a regular appointment as an organist since his years in Weimar, directed the choir and the orchestra, and he would not normally play the organ. However, he frequently must have directed his church ensemble from the harpsichord, as is documented for the performance of Cantata No.198, Laß, Fürstin, laß noch einen Strahl (Trauer Ode) in 1727. Generally, the harpsichord was employed as a continuo instrument, especially during Bach’s secco recitatives and in combination with the organ as a continuo instrument on the cantata choruses.